Explore maps and charts that illustrate how climate change, terrorism, COVID-19, and internet freedom require both international and domestic solutions in an increasingly interconnected world.

Last Updated June 29, 2023

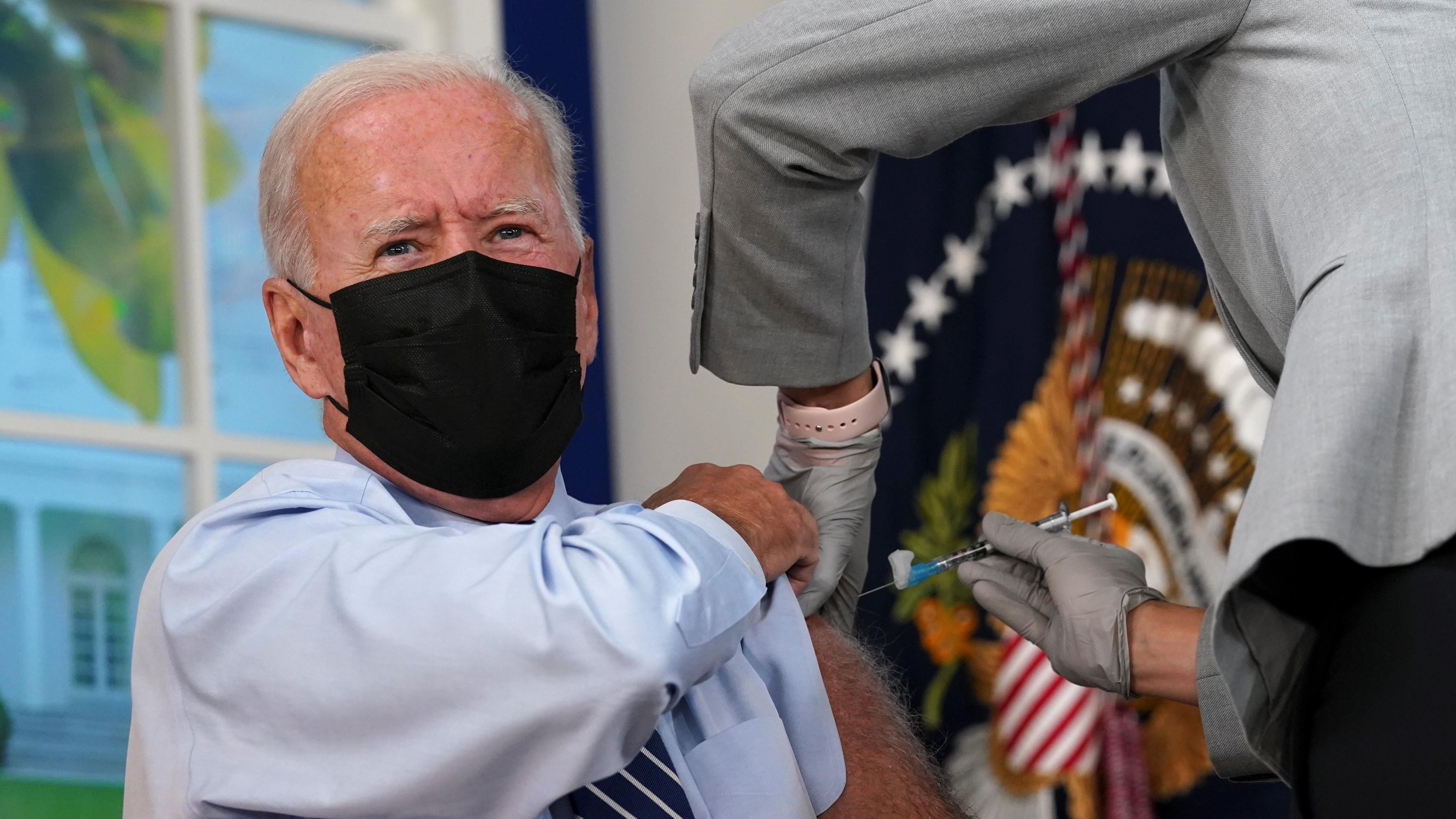

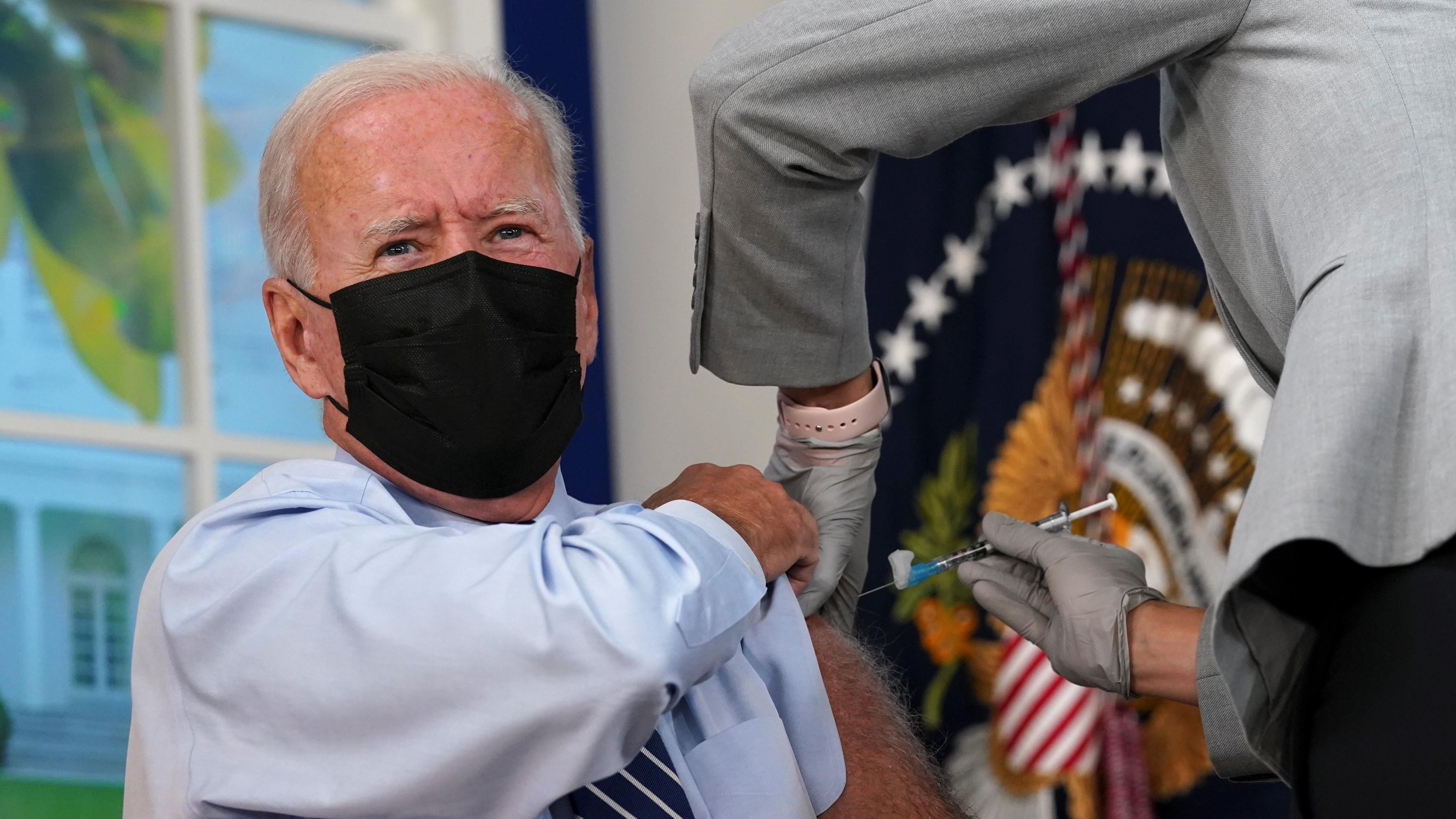

U.S. President Joe Biden receives his coronavirus disease (COVID-19) booster vaccination at the White House in Washington, U.S., September 27, 2021.

Source: REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque.

What happens abroad affects people at home, and what happens at home affects the world. That's why foreign policy—national policies advancing interests outside a country’s borders, and domestic policy — national policies advancing interests within a country’s borders are often deeply connected. In fact, drawing a clear line between domestic and foreign policy is sometimes impossible. The close relationship between the two policy areas means that policymakers need to critically assess decisions about foreign affairs while also considering the impacts on domestic issues, and vice versa. In many cases, multiple government offices need to coordinate to tackle interconnected national and international challenges. It also means that seemingly distant policy areas have more immediate consequences inside a country than anticipated.

Let’s explore a few examples of the connections between domestic and foreign policy.

When the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, the world quickly realized no one country could solve the pandemic alone. Containing the virus domestically required a clear understanding of the risks and strategies beyond each country’s borders. Indeed, in May 2021, World Health Organization Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said the pandemic “will not be over anywhere until it’s over everywhere.”

During the pandemic, governments around the world worked individually and together to produce effective and safe vaccines. Some democratic governments started initiatives that gave government funding to private companies to produce a COVID-19 vaccine. Other governments, such as those of Russia and China, nationalized their vaccine production process.

In 2021, many countries began rolling out their COVID-19 vaccination programs. During that time, many leaders found that balancing the needs of one’s country with the needs of other countries around the world was complicated.

Policy decisions about vaccines had both international and domestic effects that were often interrelated. For example, decisions about how to vaccinate one’s own population were also connected to decisions that considered the needs of other countries where vaccines were equally or more scarce. The ability of some countries to fight off the spread of the disease would have clear knock-on effects for other countries. The United States, for example, invested domestic taxpayer money to develop vaccines and then, by March 2023, exported over 687 million vaccines around the world alongside those shared at home. That decision was based on the idea that the virus’s spread in other countries could ultimately harm U.S. citizens’ health. This idea raised some controversy, as citizens debated how the United States should balance its domestic and international health efforts.

The distribution of U.S.-developed vaccines abroad can also function as a tool of soft power. Countries can use vaccine development and distribution to exert international influence or to pressure other countries. Certain countries found that the development of domestic vaccine programs could boost their international prestige. The Chinese Communist Party, to enhance their image after its initial COVID-19 response, poured funding into the development of a COVID-19 vaccine and vowed to provide the world with two billion doses after its completion. The vaccine, Sinovac, was the most used COVID-19 vaccine in the world in February 2022. But, vaccines developed by other countries soon surpassed China’s vaccine dominance. As of November 2022, the most widely used vaccine was the United Kingdom’s Oxford-AstraZeneca (in use in 185 countries), followed by the United State’s Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, in use in 165 and 114 countries respectively.

Counter-terrorism policy is another area that can illustrate how a country’s foreign and domestic policy connect. As discussed in our terrorism module, definitions of terrorism around the world vary, and are usually based on the idea that violence is driven by ideology. The rising threat of domestic terrorism in the United States is changing previous notions that terrorism only comes from abroad.

In the United States, many factors have contributed to the current terrorist threat.They often include a mix of domestic and international drivers. Lone wolves are actors without an explicit group affiliation but who sometimes cite other actors or groups as inspiration for their attacks. Many are radicalized online and mobilized to carry out violence quickly. These can include U.S. citizens and residents who attack based on varied motivations. Terrorist networks can also cross borders, including by leveraging the borderless online space, requiring coordinated policies and security forces to track and secure against those threats consistently, and in partnership with other countries’ authorities.

Domestic terrorists can be radicalized abroad and still attack at home, so the successes and failures of counterterrorism policies in one country can have outcomes in another. Debates sometimes arise about the appropriate ways to investigate suspected terrorists based on their national origins, and domestic and international suspects sometimes receive different treatment. Treating foreign suspected terrorists harshly has shaped scandals in the United States, most notably the mistreatment of foreign detainees at Guantanamo Bay. Some experts suggest treatment of foreign nationals in a country’s courts through torture or humiliation, which critics argue occurred at Guantanamo, can incite further terrorist violence around the world in response.

Policies on terrorism can influence both domestic and international threats, even though those policies are sometimes separated by different systems. Often, the smooth sharing of information between domestic and international government agencies within and among countries is critical to monitoring potential threats, regardless of their country of origin. The line between domestic and foreign policy on terrorism can be blurry, requiring multiple actors within a policy system to coordinate activities and seek to understand both the domestic and international effects of policy through strong interagency cooperation.

Another example of the connections between foreign and domestic policy is climate and environmental policy. Climate and environmental challenges require global solutions. Climate related policies can affect many elements of people’s lives, including the air they breathe, basic safety, and the availability of energy and food - thus, no one country can fully contain the results of their actions within their national borders. Furthermore, as discussed in our climate module, no climate concern can fully be solved through national policies alone, and domestic decisions can influence how people in other countries live, breathe and work.

Domestic policies can help—or harm—other countries due to spillover effects. For example, take U.S. plastic reduction policies. In recent years, several U.S. states have banned single-use plastic straws. These bans aim to help lessen plastic pollution in the immediate and wider environment. Plastic waste covers forty percent of the earth’s ocean surface, and plastic straws could be swirling around for two hundred years—which is how long it takes for them to decompose. Discarded plastic can travel hundreds of miles in the ocean, so trash in the southern United States could be ingested by animals in Mexico. Single-use plastic straw bans can reduce waste in one locality, and may help inspire other regions and countries to adopt similar policies. And bans aren’t just for straws - plastic bag bans or taxes are effective in reducing plastic us, decreasing it by up to 100 percent in certain regions!

Countries' domestic policies on plastic waste can also harm other countries. Many countries export some of their plastic waste to foreign countries to be processed, known as ‘waste export’—yielding problems for receiving countries already inundated with their own waste. India, for example, is a country that receives large amounts of those exports, which is a major problem given its relatively poor practices of plastic waste management. India accounts for an estimated 21 percent of mismanaged plastic waste worldwide and 13 percent of plastic waste emitted into the ocean in 2019. This problem is international—over 60 countries export plastic waste to India, intensifying the problem. It is often rich countries that export waste to poorer countries, making the process all the more problematic.

Many countries attempt to regulate cyberspace within their borders through domestic internet security policies. Those policies can have international effects, benefiting or harming the business interests of companies abroad by governing if and how they operate inside those countries and shaping how people around the world interact and how they gain information. Known as the Great Firewall, China’s internet censorship is one of the most oppressive policies in the world, and restricts how international businesses can operate in China (banning, for example, popular companies and products such as Google and Facebook).

Internet and data regulations exist all over the world.The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is another internet regulation act active in Europe, that aims to protect the privacy of users by alerting them if a website seeks to access their personal data. Many states in the United States are adopting GDPR-inspired laws requiring users to express consent for information gathering. Such laws can reduce the freedom of businesses all over the world to mine user data from certain regions for their marketplace goals.

According to one analysis from Google, more than 40 governments engage in restrictions of online information, “a tenfold increase from just a decade ago.” For example, YouTube has been blocked in Turkey, Guatemala suppressed WordPress blogs in 2009 during a political crisis, and Iran has stifled political dissent by blocking social media platforms. Vietnam actively filters political content from social media. Because cyberspace is borderless, internet policies like these can have various knock-on effects well beyond the jurisdictions where they originate. For this reason, a true understanding of the implications of domestic internet policies requires considering how policies can impact people and businesses all over the world.

Whether a country’s national policy prevents sea animals from ingesting plastic far from where it was discarded, whether terrorism policy in one country decreases or increases terrorist threats in another, whether family members and businesses in the United States and China can communicate over Facebook, or whether countries make vaccines available to other countries, the same rule holds true: what happens at home affects what happens abroad.